The rain fell hard as I walked down the cold unfeeling street, water seeping into my shoes, passing frat houses packed to the brim with people who thought they knew what they wanted but didn’t.

I usually stayed in on Friday nights, as I preferred to commit my time to more worthwhile pursuits. A month ago, at the end of August, I had broken my first heart, and I was still trying to understand it, my pen a coroner’s tool cutting a once-breathing body to pieces. Sarah was a year younger than me, a plump yet delicious thing who naively believed that she and I would be together forever. It had pained me to do it, yet I knew I had no choice. Even as I stole her innocence on the same bed on which I had once anxiously awaited Santa, even as I had said “I love you” in the parking lot of one of the last existing Friendly’s in Massachusetts, I knew our story would only end in tears. We were a Friendly’s—delighted and delightful, always—yet knowing one day we, too, would scoop our last scoop of ice cream. Maybe she was the lifelong customer that didn’t like to think about it, but I, like the franchise, knew not even a Jim Dandy could save us.

Santa. I guess it says a lot about me, that I was the last one to have stopped believing in him. I remember how the other children mocked me, how they would ask me if I had completed my Christmas list, if I had sat in his lap at the mall and if I felt his erection, their eyes aflame with derision. Others would simply walk up to me and say, “He isn’t real.” To this I would reply, “He is real. My mother would never lie to me.” How the children would laugh.

Yet I missed those days. Longed for them, even. I missed the dazzling innocence, the sated joy, before I had learned it was just another lie, another manufactured happiness, much like the raucus laughter of my drunk peers as they stumbled back to their dorms and apartments, the liquor convincing them that these were, indeed, the best days of their lives.

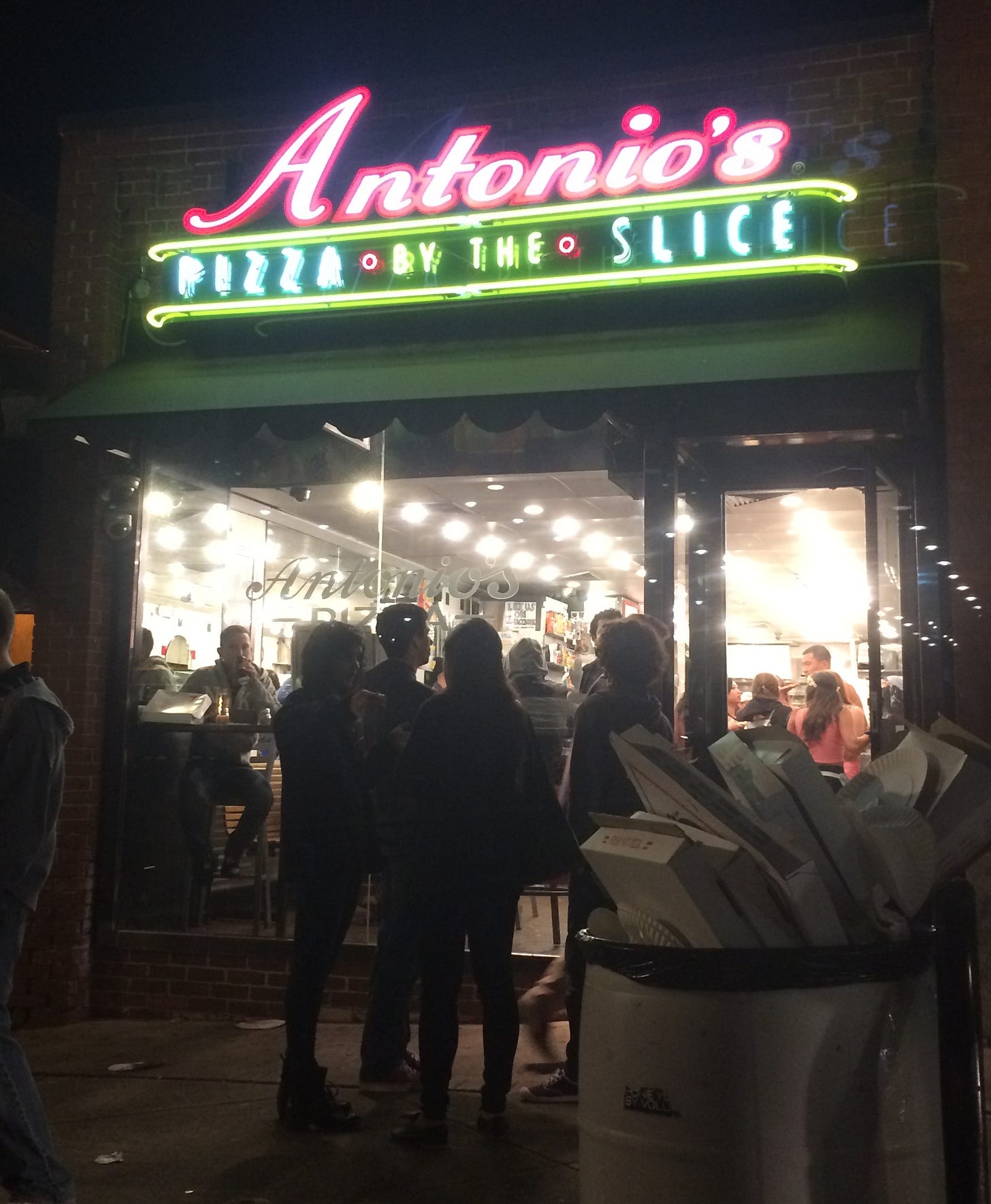

The pizza shop was wedged between two bars that I wasn’t old enough to get into, but that I wouldn’t have wanted to get into anyway. It shone like a beacon in the night as dozens and dozens of inebriated heathens unable to end the night with drunken, meaningless sex converged upon it, droplets of grease filling the emptiness in their hearts.

I kept my hands in my pockets as I approached the shop, passing a group of friends who were standing around a girl, a curvaceous minx who was passed out on the sidewalk. I laughed, and continued on. A decade from now, I was certain, The Night She Got Her Stomach Pumped would be her go-to story when she reminisced with her wine-guzzling girlfriends about her university days. She would, of course, leave out the less savory details, like how her big toe was bleeding, how a fleck of vomit clung to the corner of her mouth, or how the crop top that suffocated her voluptuous body had nearly slipped down to her ribs.

Across the street from the pizza shop loomed a church, keeping watch over the godless activities taking place below it. I wondered how many of the students stumbling before it, screaming unintelligible things into the night, had been raised with faith. A good amount of them, certainly, had affirmed their faith during Confirmation. But now the only wine the girls drank was Barefoot, Advil their only Sunday morning Communion. I had questioned the very existence of God at a young age, though it broke my mother’s heart. She told me that she felt his presence all around her, that she could feel it in the laughter of her children. I asked her if He was so good then why did my father leave her for a colleague twenty years his junior, and she broke down in tears. She simply insisted that He existed, but I just shook my head, thinking of hunger and cancer and poverty, remembering that she had said the same thing about Santa.

I pushed my way into the pizza shop, its small floor packed with drunken students screaming over each other, all intent on making the next joke. I ended up in line behind a single girl. I couldn’t see her face, but she was undeniably stylish like a Bratz doll. Her white pants coalesced around a galactic ass, and her mahogany curls cascaded over her exposed shoulders like flowing water off a cliffside. Pink ribbons adorned her hair like a present on Christmas morning, a present I was all too eager to rip open.

“Could I have two slices of cheese?” She said. The employee held up two fingers and she reached into her pocket, pulling out her wallet and opening it only to find nothing there. “Oh,” she said, crestfallen. “I thought I had a twenty.”

“Sorry,” the guy said.

“Could I have just one? Please?”

“I’m not gonna give you a piece just because you’re hot.”

She sighed, then turned around leave, and I nearly passed out from the beauty emanating before me. The discomfort of my soaked shoes vanished. The unrelenting noise around me was gone. It was only her, there before me, a pulchritudinous brunette with contoured bronze skin and eyes like two cups of hot chocolate, wearing a look of disappointment that made me want to seize the pizza cutter and take it to the employee’s throat.

“I can get it,” I said. “Just let me get three total.”

“Really?” She looked up at me, beaming.

“It’s only a dollar,” I said, slipping the employee three singles, and grabbing the box that he had handed me, shooting him a subtle but menacing look. Then, the girl hugged me. It was a quick hug, nothing intimate. Yet her touch alone was enough to send me back to my high school auditorium during a production of the Wizard of Oz, as my best friend launched into “If I Only Had a Heart,” as Sarah’s finger ran up and down my thigh, soft as a whisper in the starless night, yet powerful enough to conjure up a full moon.

Now here I was, surrounded by drunk people at 3 a.m., a pizza box in my hand, feeling those same feelings again, this stranger’s touch awakening emotions for me that I thought I had left behind in my hometown, on a shelf next to my yearbook.

“I’m Cassie,” she said, smiling.

“Victor,” I said. “Care to take a stroll?”

“I would,” she said, “but I don’t know where my friends went and I was supposed to walk home with my roommate.”

“I can walk you home,” I said.

“Really?”

“Of course. It’s no trouble.”

I had gone through the first two and a half months of college without connecting with anyone. My roommate was a pothead, my floormates dimwitted drunks, and my classmates more concerned with impressing their peers than stimulating their minds. But now walking beside me was a stunning girl, unpretentious, unassuming, and undeniably curvy, devouring her slice of cheese faster than I was and letting the rain bounce off her hair like it wasn’t there at all.